- Riders’ Reports…

- Honda CB450…

- Honda CB500T…

- Honda CB500T…

- Honda CB450K…

- Honda CB500T…

- Honda CB450SS…

The 1967 Honda CB450 looked okay, had done 20,000 miles and, according to the dealer, had been stored in France for over a decade. You can’t believe these people but I suggested hearing the engine running before I handed over £750. Wouldn’t you? Here began a great saga. However hard the kickstart was leapt up and down upon the bugger wouldn’t run. Dealer, two mechanics and I ended up knackered. The dealer recovered first, demanded to know how much I’d give him to take the damn thing away. Two hundred notes, muttered I. We agreed on £250 and that was how all my troubles began.

The 1967 Honda CB450 looked okay, had done 20,000 miles and, according to the dealer, had been stored in France for over a decade. You can’t believe these people but I suggested hearing the engine running before I handed over £750. Wouldn’t you? Here began a great saga. However hard the kickstart was leapt up and down upon the bugger wouldn’t run. Dealer, two mechanics and I ended up knackered. The dealer recovered first, demanded to know how much I’d give him to take the damn thing away. Two hundred notes, muttered I. We agreed on £250 and that was how all my troubles began.

For those who’ve been asleep for the past couple of decades, the Black Bomber was a big vertical twin with DOHC’s, short stroke and around 45 horses – when it was running. There was a spark of sorts at the plugs, petrol could be smelt when a plug was pulled and it turned over without making any strange noises. That about exhausted my repertoire, so I sent a letter to the Editor demanding to know what I should do next. No reply, lazy sod! I didn’t need the bike right then so left it in the garage whilst I pondered my next move.

New plugs and cleaned points – no help. Coils and leads off a car next. No better. Then an old biker down the pub gave me a useful tip. Heat up the plugs over the gas-stove. I gave the wife a right ear-full when she admitted she’d gone electric and deprived me of this useful aid to amateur mechanics. My old paraffin blow-torch was dusted off and pointed at the plugs. At last, some encouraging noises. 35 kicks later the engine was running.

The choke mounted carb needed lots of juggling to keep her from conking out. When the oil cleared out of the exhausts, the engine settled down to an 800rpm tickover. The valvegear rustled away really quietly – a combination of sophisticated torsion bar springs and very small clearances. The cylinder head’s as much a work of art as any Ducati Desmo design. I never did get to grips with the starting, needed between five and fifteen kicks to growl into life from cold.

The Honda has the pistons going up and down alternatively, giving a distinctive off-beat note rather than the even firing of a 360 degree crank employed by all those British twins. The CB’s arrangement’s supposed to make things smoother but you could’ve fooled me. From tickover up to 6000 revs the thing buzzed away like a chainsaw, the pegs and bars making my extremities go all weak.

I wasn’t impressed after taking the Honda for a quick run around our council estate. It was only when I got the revs past 6000 that the motor smoothed out and had a lovely punch that yanked my arms out of their sockets. Christ, the rev counter shot up to 11000rpm in second like there was no tomorrow.

Then there was a crunching noise as third failed to engage, the needle trying to go off the end of the gauge. I shut the throttle before the engine hopped out of the frame or the dead were awoken from their graves. Those in the immediate vicinity looked skywards in search of the dive-bomber on a suicide mission whilst I tried to look innocent. The Black Bomber has one of the nastiest gearboxes in the history of motorcycles – no feel, ten false neutrals for each of its four gears and it locked up solid whenever we came to a standstill.

This was one precarious bike in town. Hitting a junction with the gearbox jammed up whilst I waited for the lights to change, caused the clutch to overheat. I had to keep twiddling the clutch cable adjuster on the handlebar to stop it stalling dead. The motor gave off waves of heat (yes, I had changed the oil), threatening to melt in the frame. I had a terribly hard time using the bike as a commuter, just no fun.

I looked for consolation on the open road. The bike was rapid up to the ton then lost all its go; that was okay, on the kind of curving roads I loved the ton was a rarity. What really annoyed me was the front brake. A TLS drum of quite large dimensions. I thought it was a neat bit of tackle at first. At least in town, where it pulled up nicely and was very sensitive in the wet. But on the open road, fade ruled. The old alloy overheated until there was the smell of burnt asbestos. Lethal.

The first I knew of this trait was coming up to a 30mph corner at, er, 60mph. Heave-ho on the brake lever. Retardation coming in, then nothing! Oh-my-god, the whole bike went into a huge wobble as I tried to wrench it over, knock it up and make a straight line out of the corner. My life flashed before me as the suspension turned to mush. Big blancmange time!

Just to complicate matters, the survival line included the wrong side of the road and some old gent came careering around in a Fiat. Silly old fool just froze up as I wobbled across his front bumper with inches to spare. He drove right off the road. I should’ve done a runner but I pulled over and ran back to see if he needed help. He seemed to be having a heart attack, so I shot back to the Honda to rush to a telephone. The bike took that moment to refuse to start. Five minutes later some stockbroker type rolled up in an orange Jag and did the business on his mobile phone. I cleared off before he reported me!

After that little adventure I treated the bike with kid-gloves, no point hustling like a madman if the brakes didn’t work, was there? I took to doing 11000 revs in second just to see how long the engine would last. Didn’t seem to worry it in the least. I ended up backing off before the vibration did me in. It’s impossible to wheelie one of these bikes – god knows, I tried hard enough!

Added to vibration and brakes that didn’t work were piss poor electrics. They were reputedly 12 volts, probably as a concession to the electric starter (which was burnt out) but the front light wasn’t bright enough to suit a moped, let alone an 110mph machine. The horn was a frog-like croak that was drowned out by the open megaphones (the bike sounded best on the overrun). The indicators were missing. The worst bit by far was the battery which burnt out every three months. Unlike British bikes of this era the engine couldn’t be kicked into life on a dead battery. Also the leads kept falling off, causing the motor to conk out. Bitch!

Whilst I’m moaning I’ve got to mention the god-awful final drive chain (they had the good sense to use gear primary drive). I’ve never come across such an ill-designed, quick wear piece of knicker elastic. I couldn’t believe that the new chain I fitted lasted only 3500 miles before the adjusters were at their limit. I wasn’t having any of that nonsense, took two links out of the chain. I felt pretty clever at getting the better of the beast. For a whole two weeks. Then the chain broke.

I thought the crankcase was broken open but the noise came from the clutch pushrod. What kind of moron designed an engine with the rod a few millimetres from the chain? The local Honda dealer just laughed when I asked if he could order one for me. An old codger made one up out of silver steel for a tenner.

Two weeks later massive quantities of oil started seeping out of the clutch pushrod seal. You can buy these from bearing factors and they can be fitted without splitting the crankcases. Buy two, because it’s quite easy to batter them to death when knocking into the crankcase! A lot of Hondas of this era have similar problems, some broken chains knock out holes in the crankcases – it’s certainly a good idea to whip off the final drive sprocket cover before handing over good dosh.

The Honda was over 25 years old when it fell into my hands. What they were like when new I can’t say. The bike had a fair turn of speed (better than a GS450E), handled okay and was economical (65mpg). But it was a pain in the arse, lots of little things going wrong, nasty brakes, enough vibration to set off my dental fillings and a complete service needed every 500 miles. In other words it was getting old and worn, in need of either a decent rebuild or a caring owner who was going to spend most of his time moaning about the way they make modern bikes. I had a year and 9000 miles worth of biking but I had more fun on my old Honda SS50 moped. Still, it sold quickly for £450.

Alan Jennings

Return to Contents for CB450’s

CB500T (1974)

The thing emerged from the garage and I was, for once, lost for words. What sort of person would use a CB500T engine as the basis of a trail bike? Huge knobblies, lightweight forks with a tiny SLS wheel, much hacked about frame, alloy guards and a tiny single seat. If it had not had Honda on the tank I would not have known what the hell it was. In style, it was very like those Brit twins of the sixties which for their sins were occasionally shoehorned into lighter frames and running gear, and then let loose on some unfortunate hillside.

The clock, a small custom item, showed 620 miles. The engine had the top end redone and been blueprinted. So, a virtually new engine not even run in, if the owner was to be believed. On starting up the engine sounded noisy, all sorts of top end rattle. This soon went away as the engine warmed. A test ride showed the bike pulled much better than expected, due no doubt to the vast amount of surplus weight stripped off.

Although the engine and cosmetics were okay, a little tidying was needed, like rewiring. I also fitted foam grips and rubber mounted various bits and bobs. The vibration eased as the engine was run in, but is still there. The bike also felt a little unstable at low speeds, which I put down to the knobblies. Just after the bike was run in, a dice with an XR2i showed ton plus potential….

Five minutes later I did a lifesaver look before overtaking a parked car and was perturbed when most of the right shock shot past my face at a rather alarming speed. A used pair were scored for a tenner. The newer shocks also had a little more give and the bike became more pleasant to ride. Then the front brake nipple pulled off the cable as I was coasting to a halt. An ornamental flower pot proved to be up to the task of retarding the progress of both self and bike. I started to think the machine hated me….

Rewiring proved to be more of a hassle than I anticipated, as I found some very strange things had been done. Don’t bother with those silly boxes of packaged terminals sold at motoring stores, the stuff in the Maplins electroinic catalogue is ridiculously cheap. Also worth a look is Merv’s Plastics who advertise in the glossies and MCN.

The Honda’s off road capability, or lack of it, has not been seriously tested, although riding it round my landlord’s acre of garden proves a fun way of giving the dog a run, and further freaking out of the neighbours, who for some strange reason think I am running a bike and scooter repair business in between restoring rifles. Fear and loathing in Malvern does not really have the same ring to it, does it?

With the exception of a cafe racer Commando and a mildly customised Z650, the 500 is the only seriously modified bike I have used, and it seems to attract lots of looks. Comments vary from hysterical laughter (an off road shop specialising in full bore enduro bikes) to interested admiration (a custom shop). The latter tells me of another flat track styled one, and a hardtail chop with 500T power. Keep slagging them off as it keeps prices down. Never an overly popular bike, I have had trouble getting bits from breakers.

Rubber mounting the single seat proved a very cheap and easy tack – I merely hacksawed two old fashioned doorstops of the rubber type and put them between the seat and the frame, protected by penny washers. The vibes were further tamed by fitting foam grips and thick rubber footrests in place of the serrated metal ones.

As the bike put more miles on, vibration faded until it only came in between 70 and 80mph, and then smoothed out again. Having done this speed once on knobblies I did not care to repeat or recommend the experience. It really did feel like riding on ball bearings. A change to a Metz ME33 front and Pirelli Mandrake rear made the Honda far more stable all round, even if it didn’t look so good.

Electrical problems continued to plague the bike. When purchased it had the minimum legal and practical necessities. Ignition and charging circuits controlled by an on/off switch and a brake light. A friend advised me to tear the whole lot out and start again. Gawd, I wish I had. However, the bike was needed for commuting at night, a head and tail light would come in useful.

A headlamp was supplied with the bike, so it would seem to have been an easy task. Ho bloody ho. The rear light contained not the conventional twin filament set up, but three pilot bulbs connected together (almost) by solder and supplied by a length of two core mains cable. A small but legal rear light was fitted, a cheapo main/dip switch, and we were away…..well, not quite. The switch was not really up to the job and on closer inspection the on/off microswitch fitted to the bike had only a 1.5amp rating. A bracket was made up, the proper ignition switch fitted under the tank and a better quality main/dip switch fitted. Success! For quickness, the connections were crimped with one of those cheapo crimping tools but are gradually being replaced with soldered connections.

A quick aside. When the main beam blew, the replacement bulb only lasted a couple of days….turned out to be a used bulb placed in a new box for which full price was charged! A pair of mystery misfires occurred. One caused by the horn terminal brushing the down tube. Then there was one on the right-hand pot, which would run perfectly sometimes, or not at all.

Once again the advantage of a complete rewire was shown. When I traced the fault to between the points and coil I found a previous owner had not bothered to replace a knackered bullet connector, but instead elected to build it up with solder. Putting on a proper soldered bullet took less than five minutes and ten pence, very likely less time than his bodge. Laugh, I nearly paid my poll tax. As I only have a limited amount of time to work on the bike, it is a policy of gradual improvements to the electrics rather than a full strip down and replacement.

The vibes are still there. The perspex number plate disintegrated, to be replaced by a very neat aluminium one. The very next day the bike was pulled. Was it the row caused by the velocity stacks and straight through pipes? Doing 50 in a 40mph zone? Having long hair and a happy expression? Nope, the alloy plate was undersize. I am surprised that el fuzzi didn’t point out it was over 15 degrees from the vertical.

In conclusion, I must admit I like this bike. It is often mistaken, due to the sound and styling, for a Brit. I think the mass and performance of the 500T as stock are 430lb, 105-110mph and circa 50mpg. At a guess, I reckon this one must have lost at least 50lbs, probably nearer 75lbs. With subsequent improvement in overall go and handling, not to mention looks – the 500T as bog standard makes a CX look (nearly) pretty.

Since the above was written the Honda has put on another 2000 miles. S & Bs have replaced the pretty but useless bellmouths, leading to easier starting from cold and less paranoia about the engine. To my surprise, a plug chop showed the standard jets to be delivering the right mixture. So far they have dealt with bellmouths, a 2-1, the present high level pipes and the S & Bs without a hitch.

A new tail light and number plate assembly has been fitted off some unknown Jap, and a rear seat and pillion rests from an even more obscure source. The servicing is very boring – points and valves were spot on, little or no oil is used and the only problems have been due to some of the custom parts.

The forks twisted in the yokes and were set up quickly and cheaply by a local specialist. Also giving a few hassles have been the supports for the custom pipes, as well as the bushes between downpipes and amplifiers…sorry, silencers. In short, a customised bike can be a pain to get parts for from a dealer. I have been most impressed by the attitude of custom shops, which seem to be run for bikers by bikers. I must confess to having thought about a CB500/XS650/Z750 cafe racer, but the doctor says I will be better in a while…

Bruce Enzer

Return to Contents for CB450’s

The 1976 machine had been in my hands for 15 years! Its unique DOHC engine was still basically stock after 63000 miles. The vertical twin motor had a mere two valves per cylinder but had junked valve springs. Torsion bars via eccentrically mounted rockers controlled valve bounce. The top end was said to be safe to 12000 revs. I never took my engine to more than 9000rpm. The small ends and pistons had something of a reputation for early demise. I changed the oil every 800 miles. The CB500T appeared to reward a caring attitude.

It was a bit of a crusty bugger, mind. Below 3000 revs truculence ruled. Between there and 6500rpm it was willing to run on torque rather than power. The off-beat exhaust note was mollified by the two into one exhaust. The merging of the uneven firing pulses produced a pleasant bark. Beyond 6500 revs serious power emerged and the exhaust snarled nastily.

I rarely did more than 90mph, even on deserted, straight stretches of Scottish roads. The motor was pleasantly smooth between 70 and 85mph but tried to imitate a Triumph twin at higher speeds. I modified the gearing, as the five speed box had always seemed screaming for an extra ratio. 90mph works out at 7000rpm in fifth and the CB still pulls off from a standstill easily in second. It made the Honda much more relaxed.

A bit of weight pruning had lowered the mass from the stock 425lbs to about 380lbs. They are well built with hefty cycle parts such as guards and a massive, ugly stock exhaust. The steel does rust after about five years, another reason for replacement.

With new shocks it was a good handler in the Scottish bends only limited by the aforementioned grounding. The odd bit of really fast riding did turn up some mild weaving but nothing that would cause heart palpitations. The Honda had somehow metamorphosed its feel into that of a seventies Triumph, with more feedback than suspension compliance.

This kind of quality is usually disparaged by the race replica crowd, who know no better. It’s useful to know exactly what the wheels are doing on wet roads because it allows an instinctive reaction when the tyre starts to slip. Those doubtful of such claims should note that I’ve yet to fall off!

The Scottish roads allowed many of the bike’s virtues to shine through. Loaded up with tent, clothes and tools, the CB still growled out its torque and power. Fuel was not affected by the excessive mass, hovered around 55mpg. More was possible under a strictly sensible right hand but I always liked to the give the Honda its head a couple of times a day. Its styling was openly derided when new. It now has the cast of a classic, often confuses old gits who given half a chance rabbit on about their British biking days. I don’t mind, a strong characteristic of the motor is that it allows a relaxed pace of travel. Out of which the texture of the day emerges. In many ways a perfect touring tool.

Comfort is also good. The bars and pegs are not stock, the riding position now more sporting – it used to be painful to hold more than 70mph. The wide bars used to cause the front wheel to twitch. The flat replacement eradicated that. The seat looks stock but has a GRP base, firmer foam and a new cover. I had no choice in the matter. The old one fell apart. It was a good move as comfort became sufficient for 300 to 400 miles rather than the 150 miles of old.

The switches, lights and horn are all brilliant. Only because I replaced the inadequate originals with something newer. The alternator limits the wattage of the front light. I’ve never found a way to make a battery last for more than a year. Rectifier, regulator and indicator boxes are all original if mounted on extra rubber mounting. Blowing fuses were a problem two years ago. Replacing the wiring solved that.

On the road breakdowns are rare even at its current high mileage. I had one exhaust clamp fall off, an interesting noise resulting. And, one carb popped out of its rubber inlet manifold which killed the motor stone dead. The pair of CV carbs were a bit temperamental, not staying in balance for more than 500 miles. Matched by the valves which needed equally frequent attention. I put it down to old age.

The oil level in the wet sump had to be watched carefully. 500 miles of hard riding could drain it. Leaks were confined to a quick wear clutch pushrod seal and the cylinder head gasket. The latter was chronic but only a minor flow. The former was easily replaced but could lose a pint in half an hour when badly worn. Anyone buying a CB500T should take the engine sprocket cover off to check this. Also make sure a snapped chain hasn’t cracked the crankcases.

The other signs of an engine about to expire are excessive rattles (the tensioner isn’t automatic but works okays) or knocks and a surplus of vibration. The latter quality isn’t easily analysed as the motor thrums quite naturally at lower revs. The only way to tell the difference between a good and bad ‘un is to try several different bikes. The engine is easy to work on but spares are rare in breakers and expensive from Mr Honda.

I’ve solved the problem by buying a couple of CB500T’s. This is not uncommon amongst CB owners. For every one on the road there are probably another five in bits. They seem either to get under the owner’s skin or be abused and dumped by disgruntled riders, who then reckon they are a load of rubbish. Maybe their build quality was very variable. More shades of British biking!

Every year I’ve taken the bike on a two or three week tour. Sometimes Scotland, sometimes the Pennines, sometimes just riding in an aimless manner. I always turn up home in one piece, sad that I’ve got to go back to working for a living. The Honda is one of those bikes that positively encourages a sense of adventure. Part of it is that I’ve set the CB up perfectly to suit my own needs. The other half of the story is the way the engine growls like it’s a live thing and the way I always feel at one with the chassis.

I don’t know that there any many good ones left now, they are all old, mostly high mileage and often in a pretty wretched state. The ones I bought for spares were in a dreadful mess even with less than 40,000 miles on the clock. Their poor reputation does mean they can be had for next to nothing. If you come across a nice ‘un buy it, change it to suit your needs and enjoy a couple of years of friendly biking.

Jack

Return to Contents for CB450’s

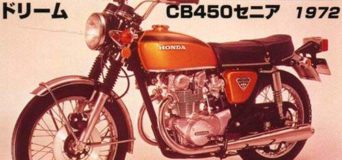

Honda CB450 Brochure

A lot has been written about the sixties Black Bomber but not so much about the seventies version. Whilst in LA for a couple of months I decided that I needed a set of cheap wheels. In the States used bikes are incredibly cheap. Partly to do with how inexpensive new ones are and also because it’s a bit of a throwaway society, where face has to be kept by buying the latest set of high tech wheels. I thought 300 dollars for a 19000 mile, 1973 Honda CB450 twin was an incredible bargain.

It looked more like a giant version of the CD175 than a classic motorcycle. The tall, DOHC engine (with its almost unique torsion bar valve springs) dominated the machine in a way reminiscent of an old British bike. The vibes that afflicted the chassis when I fired her up were also similar. The engine sounded off-tune as it idled at 1200rpm but revved cleanly enough when I played with the throttle. Into first with a BMW clunk, rev, drop the clutch and take off up the street like a scalded cat.

In LA with its excess of sun and beautiful women it was damn hard to be in anything but a good mood, so getting some kicks out of any motorcycle was a lot easier than in the cold, wet and depressed UK. The CB450 fitted in well with the place, being noisy, fast when ridden above 6500rpm and able to brake and twist around the huge whales of cars piloted by drugged up lunatics. There were all kinds of minor rules that were supposed to stop motorcyclists filtering through the massive traffic jams but I ignored them. It was unlikely that police cars would keep up and the one time I was pursued by a Harley mounted highway patrolman I left him for dead, revelling in the second and third gear acceleration.

The Honda boasted a modern front end with twin discs, in place of the rather stodgy single disc fitted as standard and a pair of longer Koni shocks. Pot-holes and poor road surfaces could be absorbed with none of the wallowing or shocks that most seventies bikes had to suffer. The Honda had a hefty tubular frame and with its improved suspension tracked true and steady even on the odd 100mph expressway excursion.

The engine had a loud 2-1 exhaust matched to a K & N type airfilter, seeming to improve on the quoted 45 horses at 8500rpm. The engine was willing to run to 11000 revs even in fifth gear, with a smoothness that was surprising in an unbalanced vertical twin, and an eagerness that belied its mere 450cc. It felt harder than a Bonnie.

Below 6500rpm there was some mismatch between carburation and combustion chamber, as it never felt entirely happy, would backfire and sulk. It also needed the best quality fuel to run properly and felt like it was going to seize when taken up the side of the huge mountains outside LA. As fuel was around 60mpg (corrected for UK gallons) it was undoubtedly running dangerously lean. In three months I did 6000 miles without doing anything to the engine except changing the oil. An eye had to be kept on the sump level and the oil also emulsified if left for much more than 500 miles.

Chatting with a dealer, trying to get him to give me a good price, he offered to add the bike to a container load he had going to the UK for just $200 as he had space to spare. I knew they were rare bikes in the UK, one in good condition bound to fetch £750 to £1000, so it seemed like a good scam.

The rareness of the bike meant I got away with paying tax on what I’d paid for it rather than what it was worth. With the pound worth 1.50 dollars I ended up paying £450 all in. Mind you, it took nine weeks to arrive at my door, by then in the depths of winter. I had little inclination to ride it then, so stashed the bike in the garage without trying to even start it. I had plenty of time to sort out the paperwork and get the bike properly registered – not a great problem if you have all the documents. There are so many great motorcycle bargains in the States that it’s worth finding any excuse to get out there with a pile of money to spend. Even the more mundane British bikes are dead cheap.

Come the spring I pulled the bike out again. It had reacted to the cold and damp by rusting and corroding, beginning to look its real age. It was also a bugger to start, eventually traced to a cracked diaphragm in one of the big CV carbs. I bodged a repair. The engine didn’t seem to run so well in the UK, needed 7000 revs to start producing power and stopped dead at 10,000rpm.

I changed the needle height in the carbs, played with the pilot screws and cleaned out the airfilter. A bit better. It wasn’t until I changed the silencer for something longer, quieter and less blitzed by rust (it was meant for a BSA A65) that the engine began to run as well as I recalled in LA. God, with intense rainstorms and the dampness creeping into my bones I really missed the American scene. I was also a bit pissed off with people coming up to me asking why I’d put a CD175 tank on a CB500T!

It was quite good as a street sleeper. Some caged lout or less knowledgeable biker would assume it was some mild old plodder and have the surprise of their life as I shot off up the road. The bike would eat Superdreams, CB650 fours, CX500s and VT500s. Plastic replicas would scream past once they had got over the initial shock but there was no way they could match my minimal running costs.

90mph was a reasonable cruising speed, with no undue vibration and a bit of power in hand to get past the ton when the need arose. With the much stronger front forks and brakes there was nothing to stop the more crazed cut and thrust techniques, although about 3000 miles into the UK experience the swinging arm bearings wore out. Some plastic crap that after a few miles, in the worn state, actually broke up. The weave that resulted almost caused me to expire. The bike couldn’t be ridden like that, for the first time in my life I had to be taken home by the AA.

The Honda dealer reckoned he could get new bearings in about two months. It had taken about half an hour to explain that the bike had absolutely nothing in common with the newer CB450D. I wasn’t willing to wait that long, ended up handing over £30 to have a pair of phosphor bronze bushes machined to fit. These are tougher and self lubricating. I put some taper rollers in the steering head, as well, because under frantic braking the forks used to shudder around the headstock. After that effort, the handling became really good, better than most Brits and up to the standards of the latest Japanese middleweights.

It was this lack of originality that introduced me to the only other CB450 owner I ever came across. He wasn’t actually riding his bike, which explained a lot, but ranted and raved over the numerous modifications that the machine sported and spluttered with indignation when I told him how much fun they made the bike to ride. I actually came close to giving him a slap, as he was becoming as nasty as a religious zealot over my total disinclination to take any notice of his point of view.

The last thing I wanted to do was ruin the useability of the Honda by fitting stock suspension, that by all accounts combined soft springs with a lack of damping, and weak forks that could be all twisted up by either brakes or bumps. I was always reassured by the CB450’s handling, loads of feedback from the tyres and the general feeling that even in extremis I could pull the machine back from complete oblivion.

I feel just as happy with the motor. There are all kinds of tales about the valves dropping, the crankshaft failing or the rings falling apart but, with the clock now reading 44000 miles, I haven’t had to touch the internals. I think the answer to this longevity is frequent oil changes (including cleaning the centrifugal oil filter on one end of the crankshaft) and regular engine maintenance. I’ve got into the habit of doing 750 mile sessions. The motor is easy to work on but the valve adjusters (rockers mounted on eccentric shafts to minimise moving mass) are rather finicky because the clearances are so small.

The electrics are the only real weak spot. Either vibration of voltage surges kill the batteries within six months. The minimal front light liked to blow its bulb and I never seemed to have enough battery power to spin the starter motor over fast enough to persuade the engine into life, although it needed but one lunge on the kickstart even when cold.

The electrics aside, it’s one hell of an impressive machine, much more so than the Superdream series and their derivatives. I can think of no other big twin that can match its durability, handling, performance, frugality and butch looks. They get to you like Italian and British bikes – I’ve sold all my other machines and got the dealer in LA to send me over half a dozen of the sods in various states of health and neglect. I refuse to leave any of them stock, though, but will be happy to sell the crappy bits to other CB450 owners.

Mark Fields

Return to Contents for CB450’s

Honda CB500T (1976)

I’d done 32000 miles on my Honda CB500T when it began to fall apart under me. Before I got my hands on the Brown Cow, she had stood for five years at the back of a garage, after grinding to a halt with an electrical fault. I didn’t complain, mind, as the rotted heap was mine for £75. Another 200 notes went west putting her back on the road, including a new rectifier. After a few teething troubles, several minor mods to the cycle parts and rigorously regular maintenance sessions every 500 miles, the Honda then surprised every one, not least myself, by running for the next six years until things went seriously wrong.

I was bounding along at about 80mph when a loud tapping noise came from the massive DOHC cylinder head. The vibes from the vertical twin motor increased noticeably, although it could never, even with only 5000 miles on the clock, be called smooth. I pulled off the road, switched the engine off, sat for ten minutes hoping that a bit of time to cool would fix it. The motor started up first go on the kickstart but the tapping was still there. Coming from the right-hand cylinder. I looked at it for a while, decided to do the five mile run home at 20mph.

By the time I was back, a lot of smoke out of the 2-1 exhaust had joined the furious hammering noise. I turned the engine off, looked the old dear over. The Brown Cow glowed contentedly, polished paint, chrome and alloy catching the dying sun. For some reason I loved the old girl.

There followed lots of hassle. I had to take the engine out to get the head off. The cams worked rockers that sat on eccentric shafts for adjustment. There were no conventional valve springs, but another rocker that worked on the underside of the valve stem, connected to a torsion bar valve spring. It must’ve cost a fortune to make and each set of valve components were matched, so they couldn’t be mixed up. Not unless you wanted a crankcase full of broken valves and pistons.

I could find nothing broken or out of adjustment. After much playing around with the right-hand components I decided that the torsion bar on the exhaust side was overstressed, not keeping the valve under total control. CB500T’s are not exactly common in breakers so it was only after phoning around the country that I found someone breaking a CB500T. The bad news was that he wouldn’t sell just one torsion valve. The good news was that the cylinder head was cracked and I could have the whole thing for £20 plus post.

A week later I had rebuilt the top end, beautifully polished, using the best bits out of the two heads. There are stories about fitting CB450 cams improving performance but those bits, in good condition, are almost impossible to find.

The CB500T’s performance is, anyway, adequate to my needs. It’ll cruise all day at 80mph in perfect comfort (with flat bars and rear-sets), put 110mph on the clock flat out and in general riding do around 60mpg. Admittedly, after 80mph acceleration’s very slow and needs a long straight to make its top speed. Below 6000 revs the off-beat nature of the engine’s combustion process makes the bike feel rather nasty but there’s plenty of grunt and it can be ridden down to 2000 revs in top (fifth) gear.

I’d pulled off a lot of the excess metal (just the stock exhaust must’ve weighed about 40 pounds) so with less than 400lbs up, there wasn’t much need to play games on the gearbox, plenty of power to run along in fifth most everywhere. After 6000 revs the power pours in hard to about 9000rpm, when the vibes start to blitz the chassis. Certainly, I had no trouble blowing off yobs on CB400 Superdreams and I even showed a GS450 owner my exhaust pipe on one occasion. Such is the reputation of the CB500T that any time I burn someone off, even if they are on a restricted 125, they go berserk, grievously insulted to be put in their place by such a period piece of seventies Japanese engineering. Needless to say, I get a kick out of showing them up.

When I first bought the CB the handling was so naff I didn’t dare ride it hard. The single front disc squeaked loudly but hardly worked. The rear shocks bounced around every time they hit a minor bump. The front end was so vague that I often ended up over a foot off line. Weaves, wobbles and large oscillations appeared every time I was foolish enough to go over 50mph.

As well as the crap suspension, every bearing on the bike was shot. Unbelievable! Wheel, steering head and swinging arm bearings were promptly replaced before I killed myself. Stronger fork springs, brace and gaiters sorted out the front end, whilst a used set of Koni shocks were bunged on out back. The caliper was replaced by something out of the breakers, Goodridge hose and new fluid finally allowing the front brake to work in a passable manner, although wet weather lag and high speed fade were not entirely eradicated, but in the context of an everyday motorcycle it was tolerable.

The bike came to me fitted with OE Jap tyres, complete with cracked sidewalls, and a brief run around the block convinced me of the need to fit Avon Roadrunners immediately. The front slides a bit on greasy city streets but life of over 12000 miles at each end means that I’m happy enough with them. Cheap chains last about 8000 miles but need frequent attention. With loads of engine braking and an easy manoeuvrability, both the front pads and rear shoes last for over 20,000 miles!

With non-standard pegs and exhausts the only things left to grind out in the bends were the stands but the prongs were easily cut back. The bike had a slightly top heavy feel, all that mass in the cylinder head, but it only took me a few weeks to become used to it. After that I found I could throw it about with gay abandon, taking her over right on to the edges of the tyres.

Keeping on the power in third and fourth, completely dominating the bike with my muscle, allowed country roads to be attacked with great gusto. The tubular frame was strong enough to stop any weaves or fork pattering that turned up from going out of control and the overall impression was of a surprisingly assured motorcycle (much helped by the BMW-like riding position I’d achieved with the modded bars and pegs).

Comfort was okay, good for about 150 miles, when it was about time to start looking for some more fuel. The most I did in a day was 600 miles, part of a 5000 mile tour of the UK. It doesn’t like much weight on the rack, so I was forced to rely on a pair of ancient Craven panniers. The original seat was recovered at 30,000 miles – I like its shape too much to replace it!

One thing to avoid is pattern parts. A set of points lasted only 3000 miles against 15000 for the Honda items. I know someone who fitted pattern pistons that were holed within 2000 miles. Despite all the nasty things written about these bikes, the original Honda components are very strong.

After the cylinder head rebuild I did another 13000 miles. I did decide to take it a bit easier, keeping the revs well below 8000rpm and not cruising for any length of time at more than 75mph. With 45000 miles on the clock the engine’s still running well, with no tell-tale increase in economy or vibration presaging its demise.

The electrics have become a bit precarious again, the battery burning off acid every time I go on a long run and the odd bulb blowing. It probably needs a new rectifier. The finish is still good, the cycle parts and frame paint still original if polished every week. It all seems very strongly built, with none of instant rusting of horrible things like Superdreams. I have an overall impression of good build quality.

The last one was built in 1977, so that means at least 18 years of abuse. I’ve recently seen two others out on the road in good condition. They either seem to last well or have been consigned to the scrappy very quickly. I even saw one advertised for £1500 but he didn’t sell it for that and wouldn’t take my offer of £400 over the phone.

£500 seems the most you could expect to pay for a reasonable one, with something tatty but running going for £250. I’ve got a GPZ500S for my serious riding now. Great fun and equally full of character but it’s the old Honda with its unique appearance that grabs the attention when parked up.

Geoff Wilson

Return to Contents for CB450’s

The UMG’s covered CB450’s at length in the past, partly down to editorial blessing and partly because, despite what you may read elsewhere, they are a good bit of tackle. This coverage alone is responsible for the healthy numbers coming in from the American importers. Whilst sixties Black Bombers remain rare and expensive, the seventies version hasn’t seen its price go wild and there are many available with less than 30,000 miles on the clock.

The UMG’s covered CB450’s at length in the past, partly down to editorial blessing and partly because, despite what you may read elsewhere, they are a good bit of tackle. This coverage alone is responsible for the healthy numbers coming in from the American importers. Whilst sixties Black Bombers remain rare and expensive, the seventies version hasn’t seen its price go wild and there are many available with less than 30,000 miles on the clock.

In my travels I came across a red 1971 scrambler version! It may seem a little insane to consider going off-road on a bike like the CB450, but such styling exercises were all the rage in the States back then. Basically, it was a stock CB450K with a smaller tank, high bars and high-rise exhaust system. Much more of a road bike than trailster, perhaps capable of the odd spin on gravel when a desperate urge arose.

The bike was basically intact but rather tatty around the edges – lacerated seat, dented tank, rusty exhaust, worn out knobblies, frayed cables, loose swinging arm bearings. But the motor fired up on the electric boot, sounded remarkably quiet at tickover (always a good sign) and didn’t spit out any smoke (check the breather as well). Mine for 750 notes and a wicked smile from the dealer that seemed to indicate I’d just been done.

He delivered the bike to the humble squat, the presence of half a dozen roaming wolves (well, big dogs but they looked indistinguishable to me) soon took the grin off his face. The bike was hauled up into the house and fixed up over the next couple of weeks.

It’s dead easy to leap on a CB450, toddle off around the block and conclude that it’s a bit of an old monster. It has a massive four bearing, 180 degree crank, with pistons that move up and down alternatively. This gives perfect primary balance (unlike the old Brit designs) but there’s a torque reaction along the length of the crank. This is rather like big BMW boxers, insofar that the engine shakes away for the first few thousand revs. Come 6000 revs, power pours in and the motor smooths out to a degree where it’s quite happy cruising at 9000rpm! The bike was quite amiable at lower revs, with a surprising amount of torque. This upside down nature of the engine must’ve confused the hell out of old Brit twin riders in days of yore!

Incidentally, and somewhat conversely, with the carbs balanced perfectly and a decent set of plugs, it’ll happily tick over at 600 revs with an amazing lack of engine noise. Part of that must be down to the superior design of the cylinder head. DOHC’s work rockers that sit on eccentric spindles for adjustment (the screws easily accessible on the side of the engine) whilst the normal valves were junked in favour of torsion bar springs which act on the valves via yet more rockers.

This is a complex and expensive way of allowing engines to rev high whilst minimising the actual moving masses in the valvegear. All sets of rockers and torsion bars are matched and if they get mixed up it results in dropped valves. Honda didn’t incorporate this into their other designs (CB500T apart) because valve spring technology moved on (and wasn’t so stressed in four cylinder designs) and the sheer expense of it made it less than viable.

But there’s no reason to consider the CB450’s top end as anything other than excellent. I found that I could string third gear out to 12000 revs without it feeling like it was about to explode. The engine was never sedate nor remote. Every twist of the throttle resulted in a change of exhaust note and alteration in the way the motor, er, thrummed! The weird thing was that after a couple of weeks the vibration disappeared completely. It was only when leaping on to a more modern machine that I was astounded by the new levels of both smoothness and chassis sophistication. If you like your bikes a bit rough and ready the CB450 will appeal, if you want smoothness to the point of blandness, look elsewhere.

As with the vibration, first impressions of the handling were of top heaviness but this soon faded, replaced with a useful amount of feedback from the tarmac (springing was taut enough to suggest an upgrade) and, dare I say it, a security in the ride that had me flicking it around with more abandonment than many a modern bike!

Of course, whilst the power was always meaty and brutal it was only, at the end of the day, forty or so horses. This stressed the relatively modern Avons not one jot, allowed me to push along at extremes that would have modern bikes tied up in knots due to the sheer excess of goodies at the end of the throttle cable. Wheelies, wheelspins, etc., were entirely foreign to the CB450 – indeed, more likely to break the clutch or gearbox than achieve interesting forward motion.

If there was one area in which the bike showed its age it was the transmission. A five speed gearbox that had not taken 26000 miles of abuse at all well. What can you say about old Honda gearboxes? Crap, just about sums it up. It took me two months to really get to grips with the box, and then only by starting off in second whenever possible because getting from first to there was close to impossible without becoming stuck in neutral.

Even when I re-learnt the tap dancing lessons of my youth, the clutch was also prone to overheating in town. The plates dragged, the bike threatening to move forward until I had to apply the brake, which stalled the engine. Adjusting the clutch play at the lever helped, as long as I didn’t forget to loosen it back off when the motor had cooled down again!

The clutch pushrod seal sits next to the drive chain, gets covered in crud and lasts a mere matter of months, before half a sump’s worth of oil leaks out. It can be pulled out with a screwdriver and replaced without splitting the engine (the seals are readily available in bearing factors, buy two because it’s a bit of a job to get the new one back in straight).

I also had the chain (far from new as it was) snap on me at low speed. It can often bend the clutch pushrod and sometimes cracks the crankcases. Neither of those happened to me, I just had a three mile push back to base. The tiny engine sprocket doesn’t help chain longevity but basically it’s the same stuff they use on the 250, and therefore barely adequate. Old style chains are a messy business that will bring tears to the eyes of anyone used to modern, almost maintenance free, O-ring jobs.

As will the maintenance requirements of old, worn Hondas. We’re talking 500 miles here – oil, valves, carbs, camchain tensioner and points. I even found the starting went off if the plugs weren’t replaced (though it’s an easy job as there’s nothing in the way). The valve clearances are very fine and finicky to set despite the screws being external. I’ve got it down to about an hour for the four of them. Maybe I’m just incompetent, but every time I tightened up the locknuts I couldn’t stop the clearances closing up, so had to take this into account. If valve clearances are neglected the valves end up burning out! If you want an easy life give this bike a miss.

Neglect of oil changes isn’t possible because the gearchange gives up once the lube degenerates past a certain point. There’s also a filter on the end of the crank that should be cleaned from time to time but needs a special tool to extract it. I didn’t have it so it didn’t get done. I relied, instead, on the magnetic sump plug to pick up any odd bits of swarf floating around!

By the way, such is the frequency of oil changes that it’s dead easy to round off the sump plug – worth checking because if it has gone that far it’s likely that oil changes have been neglected. About the only good thing that can be said on this front is that even when thrashed the sump level never seemed to fall between lube changes.

Having adapted to all these needs, and become used to its idiosyncrasies, I have to admit that I found riding around on the Honda great fun! Not least because it was a bit of a street sleeper. Some poor guy on a modern bike clocking it as a rat CB500T, suddenly had the shock of his life as the bike roared off at 10,000 revs, a lovely, milk bottle shattering, howl out of the exhaust. Okay, once they got to grip with things, they would howl past on one wheel but I’d soon catch them up again in town, as the Honda was narrow and could be flicked every which way through the traffic.

Cut and thrust was limited only by the front TLS drum brake. This wasn’t the antique its appearance might suggest, was in fact quite powerful, highly progressive and a dream in the wet. The only hassle was that a few really hard stops made it overheat and then fade badly. Not total suicide as there was masses of engine braking and useful back-up from the rear drum, but it did mean I had to ride slower than the bike was capable of until the brake cooled down a little.

For the money, and considering the bike’s age, I can’t really complain about the Honda. It must have been a shocker back in the sixties and can even show modern bikes a thing or two (like 65mpg despite been ridden hard and usable handling despite weighing 400lbs). Having said all that, at this kind of age a large amount of luck’s needed to find one at a reasonable price. But worth the effort.

Dick Lewis

Return to Contents for CB450’s

Nice to find my article on the 500T – I used to write for UMG. The bike suffered 2 major blow ups after it went to a new owner, who used to use it for ‘shopping trips’ to Amsterdam…